Batteries - Move over gas, batteries are about to take over the NEM

- Dec 19, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 22, 2025

2025Q1

This is a reasonably long article, but work with us as we give context and background explaining why we are at a profound juncture in the energy transition in our local market.

It feels like yesterday, but it has been almost eight years since the 100 MW Hornsdale Power Reserve, the first large utility scale battery in Australia, was commissioned in the National Electricity Market (NEM). Since then, we have seen rapid increase in utility scale batteries across the NEM. There are currently 18 large scale operational batteries in the NEM with a combined capacity of 1.65 gigawatts (GW) and an additional 10 GW of battery projects are under construction which are expected to connect to the National Electricity Market (NEM) over the next two to three years. This avalanche of new batteries is about to change the market dynamics of the NEM.

Before we consider the market dynamics, it is important to consider demand for electricity in the NEM. By demand, we mean operational demand which, in simplistic terms, means demand net of any forms of embedded behind the meter generation in a state (think of rooftop solar, household batteries and small-scale utility scale solar). This is different from underlying demand which consists of all electricity consumed within a state regardless of where the electricity is generated, behind or front of the meter. From here on, when we refer to demand, we mean operational demand.

The chart below shows average hourly operational demand in the NEM for 2024. Demand follows the typical duck-curve whereby demand is the lowest in the middle of the day when the sun is shining, and rooftop solar generation is at its peak. Demand picks up in late afternoon and peaks in the evening.

During daylight hours, coal and solar are the dominant forms of supply, delivering more than 80% of demand. Coal powerplants have operational constraints which require them to maintain minimum generation levels to ensure that they can operate at stable levels and ramp up to supply electricity during peak periods.

Solar is a zero marginal cost generator and therefore supplies electricity as long as the sun is shining. In the middle of the day, these two players are price insensitive and continue supplying electricity irrespective of demand (and consistent with this, it is not uncommon for electricity prices to be negative during this period).

However, as we enter evening hours, the market dynamics change. There is heightened demand during evening hours as household demand for electricity picks up. As the sun sets, solar generation wanes and is replaced by additional coal, hydro, gas peakers and wind whenever it is available.

Let’s focus our analysis on the three hours starting from 6pm and ending at 9 pm. Total demand across the NEM during these hours on an hourly average basis is approximately 26 gigawatts (GW). The biggest source of supply during these three hours comes from coal fired power plants, providing on average 16 GW of electricity. Followed by gas and hydro, which combined together, provide approximately 6 GW of supply. Then, there is wind generation, which intermittently provides 4 GW of supply (on average).

Finally, the thin layer of grey icing on our stacked area chart is formed by batteries which are currently supplying 0.3 GW of peak energy demand. That, at the moment, the small fleet of batteries earns very high returns (because they are extremely nimble and are able to cherry pick the periods with the very highest electricity prices) but aren’t particularly important in terms of the overall supply/demand mix or price setting behaviour.

Unlike solar and wind, all other forms of generators have a marginal cost to supply. Coal and gas must burn fuel to generate electricity and therefore have a marginal fuel cost to supply electricity. Whereas hydro and batteries have an opportunity cost to supply. Most hydro plants in Australia have a dual purpose, to generate electricity and to store water for agricultural irrigation purposes. This creates an incentive where a hydro plant operator, when deciding when to dispatch their water, effectively needs to decide which periods will offer the highest revenues (and additional dispatch now comes at the opportunity cost of lower dispatch later). This optimisation would usually occur over a few weeks or a month (ie, I need to dispatch x gigalitres of water over this period for irrigation purposes, what is the optimal pattern of dispatch that delivers the highest electricity revenue?).

Batteries are effectively very similar to hydro, but over a shorter time horizon. Most batteries have warranties that allow them to dispatch at a rate of one cycle per day (full discharge, and this, combined with their financing/cost structures, incentivise batteries to dispatch at regular (ie daily) intervals. Thus, optimising battery dispatch (for our purpose here we are ignoring FCAS revenue) is a case of trying to charge when electricity prices are lowest (eg in middle of the day) and then deciding when in the next 24 hours to dispatch this power to earn the highest revenue. This is usually in the evening peak. Thus, a key dynamic to keep in mind in the period ahead, is that most batteries will fully cycle their capacity every day.

Prices in the NEM are set on a five-minutely interval. Each generator submits a bid stack for a trading day, specifying how much power they are willing to supply at different price bands. To arrive at a price for a given five-minute interval, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) orders the bids from each generator from the lowest price to the highest. AEMO dispatches generators in ascending order of their offer prices. The bid from the last generator that meets the demand requirement for the interval sets the clearing price for all generators (and is consistent with the all the operational/transmission constraints necessary for stable operation of the grid). During peak hours, the marginal generator is usually a gas generator. Gas has the highest marginal fuel cost and therefore gas bids to be dispatched only when the price is high enough to cover fuel costs. Hydro and batteries have historically been shadow pricing gas which allows them to rank ahead of gas in the bid stack but essentially receive the price that was set by gas. Coal bids in a manner which ensures that it is dispatched reflecting its lack of flexibility.

With the influx of new batteries, bidding behaviour and the role of gas in peak supply is about to change. Let’s bring the three hours of peak demand together (6-9pm in the chart above) and change our units of electricity to Gigawatt hours (GWh) so we can keep the physicists happy. During these three hours, coal provides 48 GWh of electricity. In the near-term, we don’t expect much change in these 48 GWh as coal is not the marginal generator and does not dictate how price is being set in peak hours. The real land grab is about to occur in the 9 GWh that are being supplied by gas and hydro each. To keep the maths simple, 10 GW of new batteries provide on average two hours of storage which unlocks 20 GWh of new supply. This new supply is very competitive compared to a gas generator from a marginal cost perspective and batteries are highly incentivised to cycle every day (or near to this). As a result, batteries are incentivised to supply roughly their 20 GWh in our peak window at a price that covers charging costs.

But the question you might ask is who is likely to make room for these colossal electric piggybanks? The answer is straightforward, it will be gas at first. Instead of shadow pricing gas, batteries will be setting prices and undercutting gas on the bid stack enabling them to be dispatched in priority and use their budgeted cycle for the day. This will force gas to make a less frequent appearance during peak hours. In fact, our expectation is that there will be some evening peaks where gas plays a very limited role, and the evening surge in demand can be met by hydro and batteries alone. For hydro, the piggybacking will shift from gas to batteries, and it will continue to shadow price the marginal generator to be dispatched albeit at lower prices.

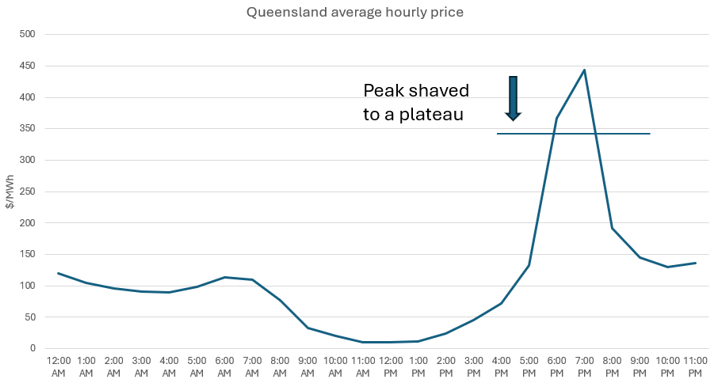

So, what can we expect from the future? This supply change will have a big impact on evening peak prices. Further, instead of an evening price spike, we expect an evening plateau as competition from batteries to get dispatched would be expected to drive prices down.

This flattening of the shape will improve the relative economics of longer duration batteries – but that’s another story.

Comments